Cholera, a waterborne bacterial infection, has continued to cast a long shadow over Nigeria’s public health landscape. Despite efforts to control the disease, it has caused considerable morbidity and mortality, particularly in vulnerable communities. In this report, CHINYERE OKOROAFOR examines the complexities surrounding cholera in Nigeria, exploring its prevalence, risk factors and the ongoing battle to tame it, among other issues.

The cholera epidemic and its devastating effects in Nigeria are not novel. According to a 2012 Pan African Medical Journal report titled “Cholera Epidemiology in Nigeria: an Overview,” published on African Journals Online, the first appearance of endemic cholera in Nigeria was in 1972, resulting in several deaths.

Another account by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the first recorded incidence of cholera in Nigeria was in Lagos with 22,931 recorded cases and 2,945 deaths.

Subsequently, it was witnessed in four northern states in the late 1970’s and about 260 people were said to have died from the epidemic; with Maiduguri, Jere, Gwoza, Biu and Dikwa local government areas affected most.

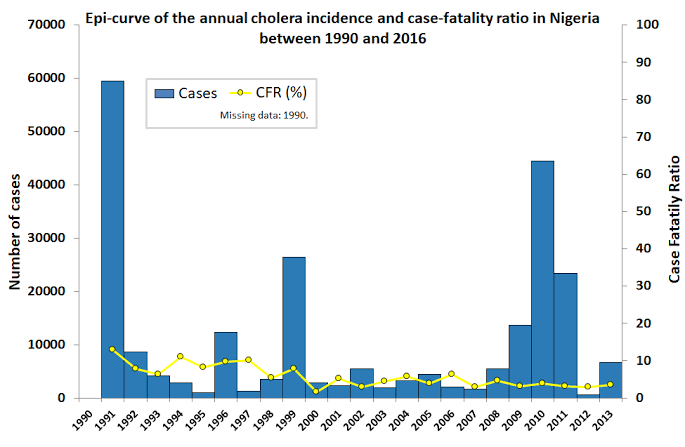

According to the Cholera Regional Platform, between 2004 and 2016, a total of 154,910 cases and 5,127 deaths were reported (CFR ≈ 3.3%).

In the North, outbreaks often spread from Nigeria to neighbouring countries around Lake Chad (Niger, Chad and Cameroon) and in the South along the Gulf of Guinea.

Continuing, the report noted that in 2014, Nigeria was most affected by the disease in West and Central Africa with 35,996 cases reported.

A view of the past decade and beyond showed that Nigeria has continued to experience recurring episodes of cholera outbreak; and the country has not been able to control and prevent it even after the 2015 United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommendations to curb the waterborne disease.

In early 2015, cholera cases were reported in 13 states of the federation, with Anambra, Kano, Rivers, and Ebonyi being the most affected. By the end of April 2015, there were 2,108 reported cases and 97 deaths and a Case Fatality Rate (CFR) rising to 4.76 per cent. The incident caused serious concern. At the end of 2015, 5,290 suspected cases were reported with 29 laboratory-confirmed cases and 186 deaths involving 18 states and the FCT; giving a CFR of 3.5 per cent.

Following the 2015 cholera outbreak, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Nigeria conducted an evaluation that informed the 2016 preparedness plan.

The evaluation identified the “hotspots” most affected by cholera, the nature of these settlements, their hygiene practices, available facilities, and water; sanitation and hygiene (WASH)-related challenges. It also concluded that no single strategy or intervention alone could control the 2015 cholera outbreak; instead, a combination of software and hardware interventions was effective.

Data from the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) showed a significant decrease in cholera cases in 2016, with only 768 incidences and 32 deaths reported.

In 2017, the cholera outbreak, according to the NCDC, a total of 5,264 suspected and 115 confirmed cases, along with 140 deaths, were reported from 16 states and the FCT.

In 2018, a total of 23,893 suspected cholera cases, including 434 deaths (CFR: 1.82%) were reported from 18 states of Adamawa, Anambra, Bauchi, Borno, Ebonyi, FCT, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kogi, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, Yobe, Sokoto, and Zamfara. This represents the highest number of incidence in recent years, with the most affected age groups being 5-14 years (24.8%) and 1-4 years (23.4%).

As of October 31, 2019, a total of 1,583 suspected cases and 22 deaths (CFR = 1.38%) was reported in seven states that included Adamawa, Bayelsa, Ebonyi, Delta, Kano, Katsina, and Plateau since the beginning of 2019.

There was no monthly report for cholera outbreak in Nigeria according to information gleaned from NCDC website for 2020.

However, a piece titled “A retrospective analysis of national surveillance data” published on the British Medical Journal website said that the cholera epidemic in Nigeria between October 2020 and October 2021 is arguably the largest in the documented history of the country, with 93, 598 cases and 3,298 deaths across 33 states. Nigeria reported a high case fatality rate (CFR) of 5.5 per cent in 2020.

In 2021, Nigeria experienced its worst cholera epidemic in recent history, resulting in the loss of at least 3,604 lives. According to the NCDC, the country reported a total of 111,062 suspected cholera cases for the year.

The figure of fatalities from the diarrheal disease in 2021 is more than the 3,103 deaths recorded from the Coronavirus pandemic since its outbreak in Nigeria in February 2020.

While 33 states and the Federal Capital Territory were ravaged by cholera in 2021, only three states did not report suspected cases, according to the NCDC data. The three states are Anambra, Edo and Imo.

The 2021 cholera outbreak, with a higher case fatality rate of 3.2 per cent compared to the previous four years, was exacerbated by the government’s focus on the Coronavirus pandemic, leading to the neglect of other diseases, including Lassa fever.

In 2022, Nigeria reported 10,754 suspected cholera cases and 256 deaths, with a case fatality rate of 2.4 per cent. Thirty-one states, including Abia, Adamawa, Akwa Ibom, Anambra, Bauchi, Bayelsa, Benue, Borno, Cross River, Delta, Ekiti, Gombe, Imo, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Kwara, Lagos, Nasarawa, Niger, Ondo, Osun, Oyo, Plateau, Rivers, Sokoto, Taraba, Yobe, and Zamfara reported suspected cholera cases,

The most affected age group was 5-14 years, with 48 per cent of suspected cases being males and 52 per cent females. Eleven states, including Borno (3,663 cases), Yobe (1,632 cases), and Katsina (767 cases) accounted for 86 per cent of all cumulative cases. Fifteen LGAs across six states reported more than 100 cases each.

Last year’s outbreak in Borno State that lasted for four months recorded 12,496 confirmed cases with 394 deaths (confirmed 288, suspected 106) from (17 September 2022 to 23 December 2022) in 17 out of 27 local government areas.

On July 2, 2024, the NCDC’s Jide Idris said a total of 2,102 suspected cholera cases and 63 deaths have been recorded across 33 states and 122 local government areas since the beginning of the year as of June 30, 2024.

According to the government data from 2020, only 14 per cent of the country’s estimated 206 million people have access to safely managed drinking water supply services.

Worth mentioning is the fact that these outbreaks are not inevitable acts of fate. They expose a deeper truth: the struggle of many Nigerians for basic human rights–access to clean water and sanitation. Imagine daily life where clean water is a luxury, and sanitation facilities are a distant dream. This harsh reality, no doubt, fuels the persistence of cholera outbreak across the country.

Meanwhile, it has been established that cholera thrives where sanitation is poor, and clean water scarce. Also at overcrowded IDP camps, a legacy of conflict and inadequate infrastructure in certain regions create a breeding ground for the bacteria. The rains, although a blessing for agriculture, can also become a curse, overflowing poorly constructed sewage systems and contaminating water sources.

What is cholera and how does it spread?

Cholera is a disease caused by the consumption of food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae.

In areas with poor sanitation and inadequate water treatment, cholera can spread rapidly, leading to outbreaks. If people do not wash their hands with soap and water after defecating and then handle or serve food, they can contaminate the food. Eating without washing one’s hands can also transmit the bacteria. Uncovered cooked food can be contaminated by flies carrying the bacteria. Additionally, cholera can spread by consuming raw fruits and vegetables that are not properly washed with clean water.

Symptoms include severe diarrhea, dehydration, weakness, muscle cramps, fever, vomiting, low blood pressure and thirst.

Other factors contributing to the spread of cholera include indiscriminate dumping of refuse and irregular sewage disposal which enable flies to carry the bacteria to water or food.

Blocked drains and leaking water pipes create environments where the bacteria can thrive and contaminate water supplies. Overcrowded conditions such as the internally displaced persons’ camps, and prisons often lack access to safe water, increasing the risk of cholera outbreaks.

Additionally, food vendors who prepare drinks such as Tiger nut milk or Zobo with contaminated water can help in spreading cholera. The Lagos State Government identified these local drinks as potential sources of the latest outbreak.

Cholera can be deadly due to its adverse effects. Upon infection, Vibrio cholerae releases a toxin in the small intestine, triggering excessive water secretion. This results in severe diarrhea and rapid loss of fluids and electrolytes. The longer a patient goes without treatment, especially when severe dehydration and shock occur, the greater the risk of death. Despite its severity, cholera results in fatalities in a relatively small percentage of cases.

Why cholera persists

The cholera outbreaks in different parts of Nigeria are often driven by different factors. What they all point to, however, is that the country has not yet taken sufficient steps to address the “epidemiological triangle” that drives cholera outbreaks.

The Global Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology Network (GIDEON) defined epidemiological triangle as a traditional model to explain how infectious diseases are caused and transmitted.

It explained that when investigating how a disease spreads and how to combat it, the epidemiologic triangle can be an invaluable tool. The epidemiologic triangle is made up of three parts: agent, host and environmental factors.

This includes early detection, better and stronger sanitation infrastructure that can withstand heavy rains as well as basic health infrastructure.

Humans act as the hosts, carrying and spreading the disease. Even after receiving treatment and recovering, individuals can still transmit the infection to others. The effectiveness and duration of cholera vaccines are limited, making it difficult to achieve long-term immunity.

Vibrio cholerae, the bacteria responsible for cholera, is ingested through contaminated food or water. The bacteria that survive the acidic environment of the stomach travel to the small intestine, where they multiply. They attach to the mucous membrane of the intestines and can persist there for years.

Environmental factors play a crucial role in the persistence of cholera. Poor access to clean, safe drinking water and inadequate sanitation facilities facilitate the spread of the disease.

To prevent and eliminate cholera, it is essential to disrupt the host-agent-environment relationship, which experts said can be achieved through the development of vaccines that will provide longer-lasting immunity, enhancement of the immune response of individuals, ensuring the chlorination of water supplies to kill Vibrio cholera and the implementation of improved sanitary waste disposal methods to prevent contamination.

Eradicating cholera and other diarrheal diseases in Nigeria requires a coordinated effort across multiple sectors. Key ministries, including water resources, rural development, urban planning and health, must collaborate. Additionally, the government needs to demonstrate political will by investing in infrastructure and health sector development.

By addressing these factors comprehensively, it is possible to make significant strides towards the eradication of cholera in Nigeria and similar regions.

Curbing Cholera in Nigeria

The Federal Government has always claimed it is making various efforts to control cholera outbreaks by focusing on improving water supply, basic sanitation and hygiene practices. However, these measures are often implemented reactively.

Following the recent cholera outbreak in the country, the Federal Government has begun discussions with the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) to secure emergency supplies of the oral cholera vaccine (OCV). This comes as Nigeria battles the disease amid a global shortage of the vaccine.

But according to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the cholera vaccine is not 100 per cent effective against cholera and does not protect against other food-borne or water-borne diseases. It is also not a substitute for being cautious about what you eat and drink.

This means that the effectiveness and duration of cholera vaccines are limited, making it challenging to achieve long-term immunity. The vaccine serves as a temporary measure, bridging the gap between emergency response and long-term cholera control.

According to the WHO, a multifaceted approach is essential to controlling cholera and reducing deaths. This involves combining surveillance, water, sanitation and hygiene efforts, social mobilisation, treatment and the use of oral cholera vaccines.

Stakeholders believe that efforts to combat cholera in the country must prioritise improving access to clean water and sanitation infrastructure.

Investing in reliable water supply systems, promoting hygiene education and implementing effective sanitation practices are essential steps toward reducing the incidence of cholera outbreaks.

The Executive Director of Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa (CAPPA), a civil society organisation, Oluwafemi Akinbode said that the recurring cholera crisis affecting thousands of vulnerable Nigerians is a direct consequence of the government’s failure to invest in the provision of safe public water supply.

While sensitisation efforts by state authorities are necessary, Akinbode said they fall short of the government inability to address the underlying issues.

Akinbode further explained that the disease, even though preventable, is particularly vicious in areas where sanitary facilities are insufficient and the availability of safe water supply is inadequate.

“The resolution to controlling cholera lay in the effective management of public water and sanitation systems. Unfortunately, millions of Nigerians still suffer an acute lack of access to potable water supply and depend on unsafe water sources for utility.

“The recurring cholera crisis in Nigeria is worsened by the increasing trend of privatisation of basic amenities, including public water supply, by state authorities. Where profit motives outweigh the intimate needs of the people, vulnerable populations suffer the most and are left defenseless against water-borne outbreaks such as cholera.

“To prevent future outbreaks of cholera and safeguard public health, political will is required. There must be an intentional and substantial budgetary investment in public water delivery and sanitation systems across the country, particularly in informal and marginalised communities,” Akinbode said.

Cholera control aligns with global humanitarian and development goals, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Reducing cholera incidence contributes to goals related to health (SDG 3), clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), and poverty reduction (SDG 1). Nigeria’s progress in these areas supports global development efforts.

Controlling cholera in Nigeria is not just a national priority but a matter of regional and global significance. By addressing cholera effectively, Nigeria can improve public health, economic stability, and social well-being, setting a precedent for other countries. The regional and global implications of cholera control in Nigeria underscore the interconnectedness of our world and the need for collaborative and comprehensive approaches to public health challenges.

Nigeria’s current combative efforts against cholera

Despite the challenges, there are glimmers of hope. President Bola Tinubu recently approved the establishment of a cabinet committee to oversee the emergency operations centre led by the National Centre for Disease Control in response to the ongoing cholera outbreak.

The Coordinating Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Prof. Ali Pate, after the Federal Executive Council at the Villa said the President directed that a cabinet committee be set up to oversee what the emergency operation centre led by NCDC is doing and for the resources to be provided, complemented by the state governments.

The NCDC is actively monitoring outbreaks and coordinating responses. They have also activated the National Cholera Emergency Operation Centre following a risk assessment conducted by authorities last week.

NCDC said the assessment showed the country was at high risk of the disease and that the fatality rate from cholera stood at 3.0 per cent.

In Lagos state which is the epicenter for this year’s outbreak, health officials are at the forefront, ramping up surveillance and deploying rapid response teams.

Treatment centers have been established, and healthcare workers tirelessly treat the sick. Public awareness campaigns are educating residents on hygiene practices and the importance of safe drinking water.

The source of the outbreak in Lagos was traced to unregulated street beverages and contaminated water supplies. However, the culprit has always rested in a combination of factors – compromised water sources, inadequate sanitation, and the opportunistic nature of the bacteria during heavy rains.

Economic impact of cholera outbreaks in Nigeria

Experts have said that cholera outbreaks in Nigeria have far-reaching economic consequences.

Its impact affects various sectors and imposes significant financial burdens on the healthcare system and households.

The surge in cholera patients during outbreaks overwhelms Nigeria’s healthcare system. This necessitates additional resources for treatment and control measures, including medications, intravenous fluids, transportation and hospital stays.

The healthcare system’s diversion of resources to address cholera care often disrupts routine services such as immunisations and antenatal care, further straining the system.

Illness and the necessity for family members to care for the sick often lead to significant work absenteeism, thereby reducing overall economic output.

The premature deaths caused by cholera represent a substantial economic loss due to the loss of future productivity from deceased individuals. Studies estimate that this factor is the most significant contributor to the economic burden of cholera.

Households affected by cholera incur additional costs for transportation to healthcare facilities, medications and special diets. These expenses can push already vulnerable families further into poverty, exacerbating their economic hardships.

Way forward

Nigerians also have a crucial role to play in breaking this cycle. Adhering to proper hygiene practices, ending open defecation, advocating for improved sanitation in their communities and holding authorities accountable for addressing these systemic failures are essential steps toward a cholera-free Nigeria.

The country possesses the resources, expertise and potential to lead in public health and disease prevention. Yet, our actions have often fallen short of our capabilities.

It is time to rise to the challenge, by adopting a holistic approach that prioritises access to clean water, proper sanitation and quality healthcare for all.

Only then can we genuinely achieve victory over cholera and other preventable diseases that continue to afflict our country.