As the dust settles over the fallout from the U.S. suspension of aid programs, the European Union has publicly stated that it cannot shoulder the massive funding gap left by Washington, a decision that has left governments across sub-Saharan Africa doing what it can to maintain essential health services.

In 2023, the United States disbursed a staggering $72 billion in aid, making it the largest single donor in the world, largely through USAID. The EU, the largest collective donor, contributed nearly $100 billion that same year, underscoring the disparity between their respective contributions.

However, as critical health and humanitarian aid programs face disruption, the EU has made it clear that it cannot fill the void.

“We will not step back from our humanitarian commitments,” a European Commission spokesperson told Semafor. “Our 2025 humanitarian budget alone stands at $1.9 billion, with $510 million allocated to Africa.” Yet, the spokesperson added a sobering reality: “The funding gap is getting bigger, leaving millions in need. The EU cannot fill this gap left by others.”

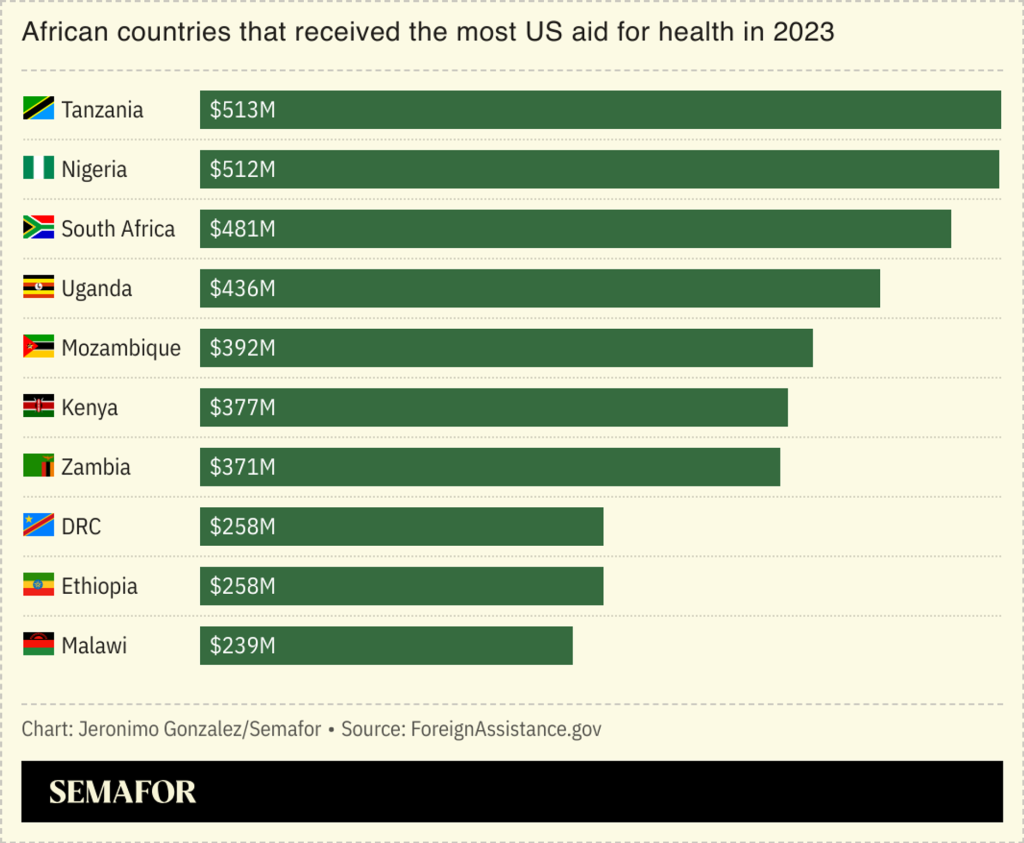

The cause of this crisis lies in the Trump administration’s decision to freeze USAID funding for a 90-day review, which has had some consequences across sub-Saharan Africa. With the lion’s share of USAID funds in the region dedicated to health services, the suspension has already led to the closure of crucial HIV treatment clinics in Uganda and halted immunization programs in Nigeria. In 2024 alone, USAID allocated over $11 billion to the region, a significant portion of which now hangs in limbo.

Governments across Africa are taking urgent steps to plug the gaps. Nigeria, for example, approved $200 million in its 2025 budget to mitigate the impact of the U.S. aid freeze on its health sector. In Ghana, President John Dramani Mahama directed his finance minister to “take urgent steps” to address a $156 million shortfall, with particular concern for malaria prevention and maternal health services.

The aid freeze has also sparked a broader political conversation. “The U.S. loses soft power with this decision,” Mahama told Bloomberg, warning that it opens the door for other countries to step in and fill the void.

Zainab Usman, Director of the Africa Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, echoed these concerns, pointing out that countries like Canada and the UK have already reduced their development assistance in recent years. Usman suggested that middle-income countries like Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa should view the suspension as a “wake-up call” to bolster their own fiscal capacities, although she stressed that the abruptness of the freeze was a poor way to initiate such reforms.

For lower-income nations, the impact of the freeze is even more serious. In seven African countries that heavily rely on U.S. aid, such assistance accounts for an average of 11% of their gross national income. The loss of this funding could have some monumental effects on their health systems, already struggling under the weight of limited resources.

Compounding the issue, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts temporarily paused a federal judge’s order demanding the Trump administration release foreign aid funds to contractors and grant recipients. Roberts’ interim order delays a ruling by U.S. District Judge Amir Ali, who had set a deadline for the funds to be disbursed by midnight Wednesday. The court’s decision gives the administration more time to respond to Ali’s ruling, which has left aid recipients and governments in limbo.

As the international community watches, the question looms: Will the U.S. find a way to restore its critical aid programs, or will African nations be forced to navigate an ever-growing crisis like nations of other continents with increasingly limited support from the global stage?